|

| Chéri Samba, "Reorganisation". AfricaMuseum, Tervuren (Photo: Maria Vlachou) |

Following the work of museums that question themselves and question us is particularly exciting, motivating and inspiring. In a rather conservative and slow-moving context, these museums are few, still very few, and it is refreshing to be able to identify that kind of leadership that deals with whatever is necessary and helps to bring about necessary changes, gradually contaminating the entire sector. It is in this type of museums that I see a true and honest effort to be useful to society, to be part of it, to be relevant.

I had the opportunity

to visit some of these museums. I start with the Tropenmuseum in Amsterdam. On my first visit, in 2017, the

directness with which it approached the country's colonial past, the creation

of its own collection, as well as racism in contemporary society shook me.

Never before had I visited an ethnological museum with this kind of discourse.

Both in its permanent and temporary exhibitions (“Colonialism in Indonesia”,

“The Future of the History of Slavery” and “Afterlives of Slavery”), the museum questioned itself and questioned us:

- How did the museum acquire its collection?

- What is our shared history of slavery?

- How do we deal with it today?

- How can we shape our common future?

- Is it possible to digest the history of slavery and all its consequences and to move forward?

On my most recent

visit, in 2022, the museum had already inaugurated the exhibition “Our colonial inheritance”. With the directness to which we are accustomed – and

notably the possessive determinant “our” in the title of the exhibition – the

museum shares an extensive and profound research into the colonial past of The

Netherlands. And there's a question for visitors at the end:

How do you get

involved?

This is a type of questioning that I have encountered in other museums as well. The recently inaugurated Humboldt Forum in Berlin questions the provenance of its collection, as well as its inventory work and the interpretation of the objects. It also invited the Nigerian writer Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie to give the opening speech in September 2021.

The AfricaMuseum in Tervuren, near Brussels, which reopened to the public in 2018, claims that its collections are the legal property of the Belgian federal state, but the moral property of the countries of origin, and shares with visitors the “rule of six” that it applies when acquiring objects:

- Is the object of importance for scientific research?

- Does it complete a collection or exhibition?

- Is it of exceptional value?

- Is it well-documented?

- In what circumstances was it acquired?

- Does it add to our understanding of contemporary Africa?

Questions of this

nature are also raised and shared with the public by the Royal Museums of Fine

Arts of Belgium, in Brussels, through the campaign “Our collection in question”. Other museums, still, interpret their collections

with a new view, having acquired a different awareness, even when, apparently,

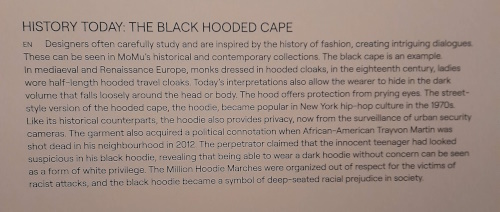

their collection is not related to the history of colonialism or racism. I am

thinking specifically of the reference I found at MoMu (Fashion Museum) in Antwerp about the black hooded cape:

used by monks in medieval times and by women in the 18th century, protecting

the person from prying eyes; in the 1970s, it is transformed into the “hoodie”

by hip-hop culture, protecting from the surveillance of urban security cameras,

acquiring also a political connotation after the 2012 murder of black teenager

Trayvor Martin (his killer claimed that he looked suspicious because he was

wearing a black hoodie, which shows that being able to wear a hoodie without concern

is part of white privilege).

|

| MoMu, Antwerp (Photo: Maria Vlachou) |

In this context, we

should also refer, by way of example, to exhibitions such as “Le modèle noir de Géricault à Matisse” at the Musée d´Orsay in Paris (2019) on aesthetic,

political, social and racial issues, as well as on imaginary revealed by the

representation of black figures in the plastic arts; “Slavery: ten true stories” at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam (2021), where the

director of the museum, Taco Dibbits, also assumes himself as a beneficiary of

slavery; or “Juan de Pareja: Afro-Hispanic painter” at the Metropolitan Museum in New York (2023), about

the painter who for two decades was enslaved by Velázquez and also his model.

The inevitable question

is: what about Portugal?

The most recent episode

is the

censorship practiced by the administration of the Centro Hospitalar do Conde de

Ferreira to the work “Adoçar a Alma para o Inferno III”, by artists Dori Negro

e and Paulo Pinto, which denounces Conde de Ferreira’s known links to slavery.

The work is presented within the framework of the Bienal'23 Fotografia do Porto

and the hospital administration, in addition to considering the references

“offensive to the memory” of its patron, considers that “there are no

psychological conditions allowing the exhibition of the work in question, since

'patients, workers and their families feel affected' by the question 'how many

enslaved people is a psychiatric hospital worth?'".

This is not a museum,

but it seems that even in museums there are still no “psychological conditions”

for certain reflections and practices. Or there is no will, sense of

responsibility, awareness of urgency. It occurs to me that, in January, when

Lonnie Bunch (first black secretary of the Smithsonian Institution and first

director of the National Museum of African American History and Culture) was at

Culturgest, in Lisbon, to speak about “Racism in the public square” (information

and video), there was

not even one director of a national museum or representative of the Ministry of

Culture in the audience; at the symposium that followed at the National Museum

of Natural History and Science (MUHNAC), “Settling scores with racism: the

social memory of the slave trade” (information

and video) only

the Director of the National Museum of Archaeology attended. The absence of the

directors of our national museums and monuments has been a constant in several

forums.

|

| Cynthia Schimming, "No title - My philosophy, your interpretation". Humboldt Forum (Photo: Maria Vlachou) |

Thinking about some which

I attended or was involved in the organisation, I remember becoming aware of

this total absence:

- at Nicholas Mirzoeff's lecture "Decolonizing the Museum: Lessons from New York" in 2018 at RE.AL;

- at Felwine Sarr’s lecture (co-author of the so-called “Matron report” on the restitution of objects) at Culturgest in 2020;

- at the meeting Decentralise the empire, repair the future”, held in November 2022 at Culturgest;

- at the Acesso Cultura seminar “Decolonising museums: this in practice…?” in 2019 (information and recordings), which had Wayne Modest of the Tropenmuseum as keynote speaker and where the Director of the National Museum of Ethnology participated as a panelist;

- at the annual conference of Acesso Cultura in 2016, whose theme was “What? So what? Relevance of contents and simple language” and with Martine Gosselink from the Rijksmuseum, responsible for the project to rewrite the tables in her museum, as keynote speaker.

These are just a few

examples. There was more. How to explain these absences? And how can we expect

to see changes, necessary and urgent changes, if the people responsible are not

available to listen and participate in the dialogue?

We must not go further

without mentioning the work done by a few Portuguese museums. Despite the

widespread apathy and inertia, something is stirring. It is worth mentioning

here the exhibition “Plural

Lisbon” at the Museu de Lisboa (2019) or “The

photographic impulse: (un)arranging the colonial archive”, currently at

MUHNAC. Both these museums, as well as Acesso Cultura and other entities, were

responsible for bringing Lonnie Bunch to Portugal.

What's in a label?

This reflection was

provoked by a label. A label that accompanies a sculpture by Soares dos Reis on

display at the National Museum of Contemporary Art (MNAC). It reads: “Cabeça de

preto / Head of black”. I had already received comments about it from various

sources, but last week a colleague's post on Facebook sparked an intense

conversation. And that’s good. It should also be taken to other contexts.

What leaves me most

perplexed in the case of this label is that the museum understands that it is

problematic. But it doesn't act. Not with the urgency that, at least some of us,

would like. Yes, these are complex issues; yes, there is so much to do. But

there are also options to take, there are priorities and, above all, there is

an obligation to take care of our audiences, including black visitors.

In this most recent

exchange of opinions, there were the usual arguments: “we are not going to

erase history”, “people understand the context in which the work was created”,

“censorship”… And yet another: “If we changed this label, we would have to

change them all” or “We will change it when we have the opportunity to review

them all”. I would venture to say that those who used these arguments have not

followed developments and reflections in, at least, the last eight years, since

in 2015 the Rijksmuseum was the first to take the initiative to revise titles

and labels. It didn't do it by erasing history; and I learned from its work

that most of the titles of the works are not chosen by the artists themselves.

We cannot continue arguing without seeking to consult the information available

and the extensive bibliography that already exists. We cannot continue arguing from

within our bubble, without knowledge.

I don't know exactly

how much it costs to produce a new label, but I think it should be changed urgently

and, if necessary, just this one, yes! At the very least, to add – as Ferens

Gallery in Hall did in one case – “Artist’s title”. It would be the minimum and

it would be a signal from the museum to its visitors. A contextualisation

paragraph, written by the museum, would be even better. I really liked the text

in the introductory panel of the temporary exhibition “Photographs: an early album of the

world”, at Quai Branly,

and the way it deals with terminology. But, above all, the fact of

communicating their options to the visitor and being aware of their

responsibilities.

A new label for this

work by Soares dos Reis would also make it possible to review the translation

of the title. Because, as two colleagues pointed out, the translation is wrong.

In English it would be “Head of a negro”, which would perhaps allow us to

understand the seriousness of the use of the word “preto” in Portuguese without

any comment on the part of the museum. Translation (specifically, proofreading

by specialists, because translators are not necessarily specialists) is of

enormous importance. I remember the shock I felt when I noticed for the first

time that the translation of “Slave collar” in the exhibition “One museum, so

many collections!” at the Museu Nacional de Arqueologia (2017) was “necklace”.

We have an obligation to take care of objects and people.

Last year, on a visit

to the Marta Ortigão Sampaio House-Museum, in Porto, I saw the “traces” of an

educational project carried out with a school. A student’s discomfort was

recorded on the wall, underneath the painting by Aurélia de Souza entitled

“Cabeça de homem preto” (Head of black man):

“My discomfort was that

he was the only one to be described by the colour of his skin.”

Next to the work, the

museum label, where the word “preto/negro” had been erased with correction

fluid. I shivered at this gesture. I thought it was good that the label had remained

just like that on the wall, with the marks of a 21st century intervention. On

the museum's website, the title is “Cabeça de homem” (Head of a man, so I

assume that it was not Aurelia herself who gave the previous title.

There is an inertia in

the world of Portuguese museums, it is as if most of us were hiding our heads

in the sand. Knowing the difficulties, the complexities, the lack of means, we

also know that priorities are set every day, decisions are taken, investments

are made. Taking care of people, just as well as we take care of objects, is a

priority, an urgency. Being relevant is, at the very least, a matter of

survival.

More on this blog

Who’s

afraid of decolonisation?

Discussing

the decolonisation of museums in Portugal

Further reading

Não

queremos um museu só para brancos

What

can we expect from a museum director?

Offensive

Artwork Titles in Canadian Museums: What’s in a Name?

Why

the Rijksmuseum Is Removing Bigoted Terms from Its Artworks’ Titles

No comments:

Post a Comment