On 15 November I participated in the seminar “Museums

and Monuments: communicate, innovate, sustain”, organized by the Directorate

General of Cultural Heritage at the Convent of Christ in Tomar. There were four

panels: Mass media: mediating or turning median?; Strategies of communication;

Marketing and branding; Funding sources, management models. For me, it was a

very interesting seminar, especially because of the inclusion in the panels of

people who don’t work in museums and monuments and who can bring to the debate

points of view which are very relevant for all of us. That is… if we are

interested in listening, in being confronted with our practices, in acting in

order to change for better.

I would like to discuss two moments of that seminar.

The first, was journalist Paula Moura Pinheiro´s speech in the first panel,

“Mass media: mediating or turning median?”. Paula referred to the journalist’s

work and his/her role in the communication with and for a large audience. For

her, the journalist has got the role of the translator. It’s someone with a

good general culture, but aware that he/she doesn’t know everything and who,

thus, looks for the specialists and various other sources, in order to collect

information. This information is then analyzed and ‘translated’, in order to be

presented to the larger audience of non-specialists. “My programmes are not for

the specialists”, said Paula Moura Pinheiro, “and the specialists don’t need my

programmes. My programmes are for those who don’t know.” She inevitably reminded

me of the British naturalist Edward Forbes who wrote in 1853: “Curators may be

prodigies of learning and yet unfit for their posts if they don´t know anything

about pedagogy, if they are not equipped to teach people who know nothing.” She

also reminded me something I had read a few years ago in The Manual of Museum Management by Barry Lord & Gail Dexter

Lord: that an exhibition is like a TV programme, it may raise awareness, but it

doesn’t turn anyone into an specialist.

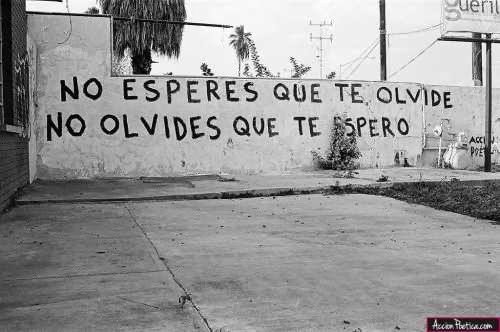

Another presentation in the first panel of the

afternoon, “Marketing and branding”, came to test the comprehension and

relevance of Paula Moura Pinheiro’s words. Advertiser Pedro Bidarra, who ran

for years the advertising agency BBDO, talked to us about “The wall of words”.

He showed us extracts from texts he had encountered in exhibitions and which

transmitted nothing to him, because… he didn’t understand them. His examples

caused much laughing in the audience, but Pedro insisted: “How come you want me

to see your exhibitions if you create yourselves such barriers to

communication? It’s no a lack of interest on my part, I would really like to

visit, but I feel that your offer is not for me, it was not produced with me in

mind.”

Pedro Bidarra’s texts were very well chosen; which

doesn’t mean they are hard to find. The discourse of the majority of our

museums is a conversation among specialists. A enormous effort is being made in

order to gain our peers’ approval and applause. Where does this leave the

audience, the people, and our relationship with them?

A couple of weeks ago I wrote about the way the euro-barometer results were received by many in our sector and I was asking if

these results are ever going to make us question our practices or if we will

continue blaming people for lack of culture, ignorance and lack of interest.

I think of the seminar in Tomar and the impact those

two presentations, Paula Moura Pinheiro’s and Pedro Bidarra’s, may have had (or

not) on the way museum professionals, especially those being directors, think

about their daily practice. What was the meaning of all that laughing in the

audience when Pedro was showing us his examples? Because in that audience there

were certainly some people who had been the authors of similar texts to the

ones shown on the screen. As the Portuguese Sandra Fisher Martins, founder of

the Plain Portuguese campaign, was saying in her TEDx talk “The right to

understand”: “These documents (she was referring to public documents) don’t

fall from the sky, they are written by someone”.