To Lambrina and Sam, Eleni and Nikos

To good friends and good discussions

Last June, Sarah

Huckabee Sanders, the White House Press Secretary, was asked to leave the Red

Hen restaurant. The request was made by the restaurant owner.

In mid-August, the

invitation to Marine Le Pen, former French

presidential candidate and leader of the National Rally political party,

to attend the Web Summit in Lisbon was followed by public outcry. The

invitation was eventually withdrawn.

Both incidents raised

questions regarding freedom of speech; whether one can fight extremist

political views and address the roots of the rise of the far-right by banning

or ignoring certain viewpoints; and whether by excluding some people you don’t

also become like them yourself.

I would like to start

by addressing freedom of speech. A few years ago, I learnt from Shirin Ebadi

(Iranian Human Rights lawyer and Nobel Peace Prize laureate) that there are

limits to freedom of speech, recognised by many legal systems, particularly when it conflicts with other

rights and freedoms. Ebadi was discussing the cartoons published by a Danish

newspaper and depicting prophet Mohammed with a bomb in the place of the turban

and had specifically referred to racist propaganda, hatred or incentive to war

(attributing, in that case, responsibilities for human rights violations on

both sides).

In 1859, British

philosopher John Stuart Mill, in his essay On Liberty, suggested that "the only purpose

for which power can be rightfully exercised over

any member of a civilized community, against his will, is to prevent harm to

others.” Based on this “harm principle”, article 10 of the European Conventionon Human Rights clarifies what kind of 'harm' this could be:

- interests of national security

- territorial integrity or public safety

- prevention of disorder or crime

- protection of health or morals

- protection of the reputation or the rights of others

- preventing the disclosure of information received in confidence

- maintaining the authority and impartiality of the judiciary

Are these

straightforward concepts that make evaluation and decisions easy? Not at all,

they are full of nuances. The important thing, though, in my view, is to be

reminded that freedom of speech has got rules and limitations, something that,

to my surprise, rarely comes up when this issue is being publicly discussed.

The second point I

would like to bring up is that freedom of speech does not mean providing the

stage and the microphone. One may deeply believe in and support free speech, as

well as welcome the difficult conversations, but one should also be aware that inviting

someone to the stage and handing him/her a microphone can be a way of

legitimising false and even dangerous ideas. As mentioned in an article for Daily Kos: “Anybody has the right to stand on a soapbox in their town square and spew

whatever nonsense they desire, but that is not the same as having a right to a

microphone and a podium at a college or a university [and we may add the White

House Press Room or the Web Summit]. By inviting someone into this venue, an

institution is essentially saying that it believes that they have ideas that

are worthy of serious discussion. This alone lends an air of credibility and

legitimacy to a speaker and their ideas.”

A third point I would

like to make is that of reciprocity. Journalist Adam Gopnik wrote about it

brilliantly in a piece for the New Yorker on the Sanders/Red Hen case: “Nothing is

more fundamental to human relations than deciding who has a place at the table

- and nothing is more essential to our idea of humanism than expanding that

table, symbolically and actually, adding extra chairs and places and settings

as we can.(…) The Trump Administration is - in ways that are specific to

incipient tyrannies - all about an assault on civility. To the degree that

Trump has any ideology at all, it’s a hatred of civility - a belief that the

normal decencies painfully evolved over centuries are signs of weakness which occlude

the natural order of domination and submission. It’s why Trump admires

dictators. Theirs are his values; that’s his feast. And, to end the normal

discourse of democracy, the Trump Administration must make lies respectable - lying

not tactically but all the time about everything, in a way that does not just

degrade but destroys exactly the common table of democratic debate. That’s

Sarah Huckabee Sanders’s chosen role in life - to further those lies, treat

lies as truth, and make lies acceptable. (…) fundamental to, and governing the

practice of, civility is the principle of reciprocity: your place at my table

implies my place at yours. (…) that person has asked us in advance to exclude

her from our common meal. You cannot spit in the plates and then demand your

dinner. The best way to receive civility at night is to not assault it all day

long. It’s the simple wisdom of the table.”

|

| Pink Floyd concert, St. Petersburg, Russia, 30 August 2018 (image taken from Facebook) |

My final point is about

this “common table of democratic debate”, as Gopnik puts it. How can we explain

our stubborn insistence on being naïve and defending the “democratic” right to

freedom of speech for hate speakers, racists and those who use the democratic

rule in order to undermine it once in power. Why are we willing to tolerate the

intolerant? Haven’t we learnt anything from history?

In Why don’t we learn from History?, B.H. Liddell Hart clearly designs for us the pattern of dictatorship:

“We learn from history

that self-made despotic rulers follow a standard pattern.

In gaining power:

• They exploit,

consciously or unconsciously, a state of popular dissatisfaction with the

existing regime or of hostility between different sections of the people.

• They attack the

existing regime violently and combine their appeal to discontent with unlimited

promises (which, if successful, they fulfill only to a limited extent).

• They claim that they

want absolute power for only a short time (but “find” subsequently that the

time to relinquish it never comes).

• They excite popular

sympathy by presenting the picture of a conspiracy against them and use this as

a lever to gain a firmer hold at some crucial stage.

On gaining power:

• They soon begin to

rid themselves of their chief helpers, “discovering” that those who brought

about the new order have suddenly become traitors to it.

• They suppress

criticism on one pretext or another and punish anyone who mentions facts which,

however true, are unfavorable to their policy.

• They enlist religion

on their side, if possible, or, if its leaders are not compliant, foster a new

kind of religion subservient to their ends.

• They spend public

money lavishly on material works of a striking kind, in compensation for the

freedom of spirit and thought of which they have robbed the public.

• They manipulate the

currency to make the economic position of the state appear better than it is in

reality.

• They ultimately make

war on some other state as a means of diverting attention from internal

conditions and allowing discontent to explode outward.

• They use the rallying

cry of patriotism as a means of riveting the chains of their personal authority

more firmly on the people.

• They expand the

superstructure of the state while undermining its foundations—by breeding

sycophants at the expense of selfrespecting collaborators, by appealing to the

popular taste for the grandiose and sensational instead of true values, and by

fostering a romantic instead of a realistic view, thus ensuring the ultimate collapse,

under their successors if not themselves, of what they have created.”

|

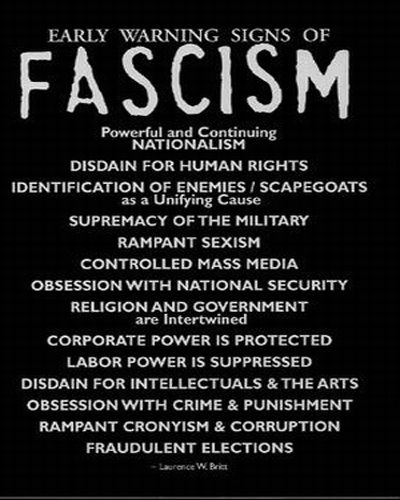

| Image taken from Facebook |

Trump, Putin, Erdogan, Orbán, Kaczýnski, Le Pen, Farage, Bolsonaro… The list may be long… Can we afford to pretend being naïve in 2018? Stephanie Wilkinson, the Red Hen restaurant owner said that “this feels like the moment in our democracy when people have to make uncomfortable actions and decisions to uphold their morals.” British-Indian journalist and academic Ash Sarkar recently wrote in the Guardian that “This isn’t just a culture war” and urged for a radical anti-fascist movement “right now”. She said: “We need a truly radical anti-racist network that’s capable of mobilising mass opposition when the far right march, as well as being able to embed itself in communities to frustrate the far right’s ability to present itself as the champion of a downtrodden working class. (…) It’s important to recognise that opposing racism isn’t just about presenting an alternative set of values; it’s about looking at how the far right play on people’s hardships in order to nurture a sense of enmity between white people and those racialised as migrant. (…) By addressing the immediate economic conditions of the neighbourhoods around them, anti-racist activists can bring together seemingly opposed communities and close down the gaps where the far right are able to organise.”

Still, for me it is also

about Culture. As I am heading to the Warsaw Forum - where we shall discuss

“Audience Engagement, Cultural Policy and Democracy” - my thoughts are exactly

about our role as culture professionals in making room at the table for those

who feel excluded, threatened, hopeless and forgotten; in helping people to

feel empowered and able to imagine; in making them realise what they can do,

both individually and collectively, even on a small scale, in order to build

better communities, a better democracy. Free from fear.

We can’t afford to

pretend being naïve in 2018.

Still on this blog:

More readings:

João Miguel Tavares, Marine le Pen na Web Summit - será quepode?

Rui Tavares, Le Pen non grata em Portugal? É a soberania nacional

Fernanda Câncio, Sim, eu censuro Le Pen. Dão licença?

No comments:

Post a Comment