|

| Image taken from LUCA - Teatro Luís de Camões Facebook page. |

The Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge is one of the best-known university museums. Its current exhibition Black Atlantic: Power, people, resistance questions us: “Which stories get remembered, and why?”. The museum states that this exhibition explores some new stories from history, questioning Cambridge's role in the transatlantic slave trade.

In 1816, Richard Fitzwilliam donated large sums of money, literature and art to the University of Cambridge, which gave birth to the museum. The donations were made possible by the enormous wealth of his grandfather, Sir Matthew Decker, a Dutch-born English merchant who helped establish the South Sea Company in 1711, responsible for the African slave trade. Responding to a need and a demand from part of the society – but also its own, it seems to me – the museum puts the finger in the wound, questioning itself and its contribution to the perpetuation of a certain History.

It is common to hear people argue against “the erasure of history”. I always get the feeling of a reaction that is too superficial, coming from people who are too comfortable, who don't truly question which history has been erased. Last summer, news of the acquisition of the painting “Bélizaire and the Frey children” by the Metropolitan Museum of Art went around the world. Bélizaire was an enslaved child and his figure had been erased from the painting, for reasons still unknown. Restoration work in 2005 revealed it again, and the Met acquired the painting “as part of its larger effort to reframe how it tells the story of American art.” This also reminds me of Worcester Art Museum’s initiative, back in 2018, to include labels that referred to the association of people depicted in portraits to slavery, “drawing attention to the connections between art, slavery, and wealth in early America”. It is to these erasures and distortions that the work of British artist Barbara Walker Vanishing Point 29 (Duyster) (2021) also refers. But it's not this erasure of history that bothers some people, that's not what they are talking about. Our sensitivity is rather selective; our fight for History, for Art, for freedom of expression too.

Image taken from the newspaper The Guardian.Last May, Dori Nigro and Paulo Pinto's installation Adoçar a Alma para o Inferno III, part of the Porto Photography Biennial, questioned us: “How many enslaved people is a psychiatric hospital worth?”. The Conde de Ferreira Hospital Centre, where the work was installed, is one of more than 100 institutions that were supported by Joaquim Ferreira dos Santos, Count of Ferreira, with money resulting mainly from the trade of enslaved people between Angola and Brazil. On the very day of the inauguration, the executive administrator of CHCF Ângelo Duarte ordered the closure of the room where the work was located, citing the potential discomfort that this could generate in a community that is home to many patients”. This censorship did not really seem to bother our society, starting with the cultural sector itself. I read at the time that the Biennial received emails of support from Porto City Council, the General Directorate of the Arts, the University of Porto and other partners. I also read an open letter, which I think was an initiative of UNA – Black Union of the Arts. But I felt that, for the most part, as a sector, we didn't really feel uncomfortable, we didn't publicly express our solidarity to our colleagues, neither as individuals nor as institutions, we were too silent.

Therefore, I found somewhat

ironic the controversy

provoked in that same city of Porto, and discussed by several colleagues in

different parts of the country, regarding the permanence or not of the statue

of Camilo Castelo Branco and Ana Plácido in front of the old Prison. I am not

interested here in discussing the disastrous management of this matter by the

Mayor of Porto. I'm not even going to repeat what

I have already shared about challenging statues in the public spaces. I am

interested in discussing our concern with freedom of artistic expression

or with “erasing

history” or, even, with the

opinion of the remaining residents of Porto. Once again, our sensitivity

proved to be very selective and we, once again, not very honest.

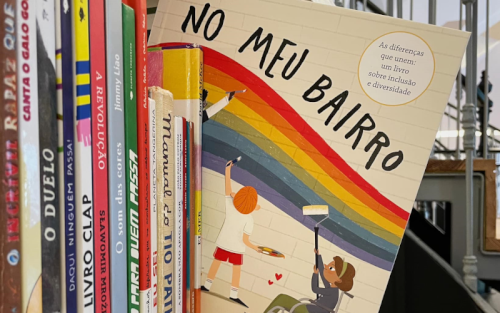

A few days ago, there

was yet another attempt at censorship, at the launch of the book “No meu bairro”,

by Lúcia Vicente. The neutral language used in the book bothered some people,

who felt they had the right to interrupt the event, to silence the author. Lúcia

Vicente told Público that "there were seven people in the audience who

had come to destabilise or directly question the book, showing their

displeasure. Which seemed perfectly acceptable to me, until the person with the

megaphone came in"... This time, I saw with some emotion and hope the

neighbouring Teatro

do Bairro Alto to publicly expressing its solidarity. Days later, LUCA

– Teatro Luís de Camões also took a stand; perhaps more discreetly, for

those who were not aware of the incident, but unequivocally.

We may think that we are far from the very serious situation experiences in the USA in recent years, with repeated (and successful) attempts to censor books in school libraries, which more recently have also affected public libraries. Initiatives such as the Banned Bookmobile Tour or Books Unbanned fight against the silencing of authors and stories, while the Chartered Institute of Library and Information Professionals in the UK recently issued new guidelines for its members stating that “In a polarised world, it is important our sector is clear in its opposition to censorship.”

I was saying that we may

think that we are far from these very serious situations. Should I remind you

that, just a few years ago, it was said that Portugal was immune to the extreme

right? It is our silence and relativisation, it is the way we normalise certain

acts and discourses, that gives space to the enemies of democracy. Our defense

of freedom of expression and the non-erasure of History must be informed,

permanent, unequivocal. And it should really – or rather mainly – exist when it makes us leave our comfort zone.

No comments:

Post a Comment